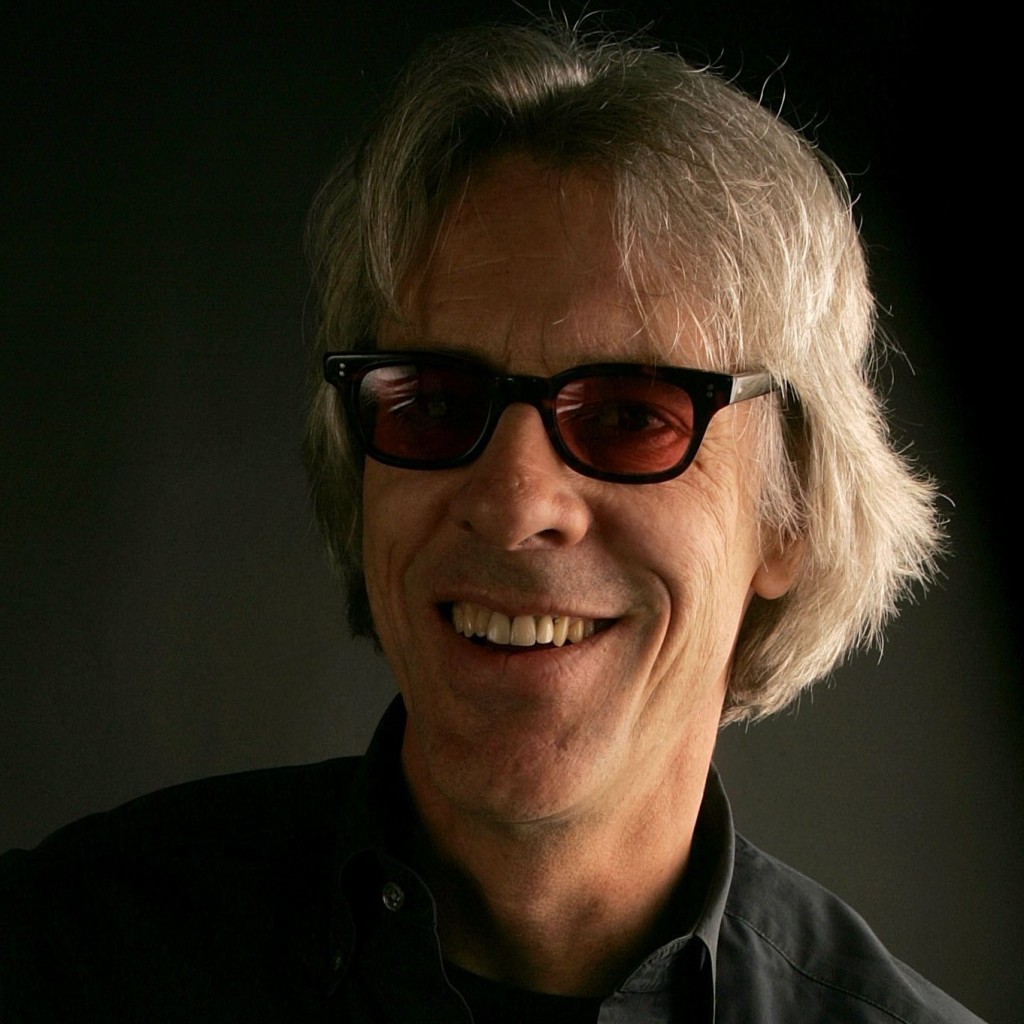

Police-man Still on His Beat

An Exclusive Interview with Stewart Copeland

– Interview by Craig Hunter Ross –

Widely regarded as one of the best rock drummers of all time, former Police stalwart Stewart Copeland grew up the youngest of four sons to a CIA man and his archeologist wife. He spent his formative youth at various exotic locales in the Middle East as well as a variety of other foreign and domestic outposts because of his father’s work.

These excursions around the world would one day play a role in Copeland’s development as a musician. So would his uncanny ability to play the drums right-handed despite being a natural lefty. The unique beats the drummer developed not only helped set himself apart from his English and American counterparts, it would be instrumental in driving the unique sound that one day would take his band, The Police, to the pinnacle of success.

It would take Copeland, guitarist Andy Summers and bassist Gordon Sumner (aka Sting) just six years to conquer the world. Then it was over. As each member went their separate ways, the drummer ignored his pop music past to pursue a career as a composer. Today this acclaimed artist and Grammy Award winner is one of the most sought after composers and collaborators in the world, as evidenced by his thirty plus scores for film and television, not to mention his forays into opera and ballet.

Ever the innovator and Renaissance man, Copeland’s latest project saw him commissioned by the Virginia Arts Festival to create and perform a score for the 1925 silent film classic, Ben Hur: A Tale of Christ. It will be performed live on stage – along with the film itself – with the Virginia Arts Festival Orchestra on Saturday, April 19.

On Tour Monthly recently sat down with the former ‘Klark Kent’ to discuss his heroic deeds in music and how ‘strange things happen’ when you are Stewart Copeland.

ON TOUR MONTHLY: In your biography, Strange Things Happen, you detailed a time when you are at the American Embassy Beach Club. Your friend and band mate Pete counts off the first song. You said you never heard him finish and that “Whatever we had rehearsed is gone from my head, but the motor has started.” Does that still happen to you when you play live and does that also, in a way, describe how your musical life has gone?

Stewart Copeland – It’s a lot more exciting than it was when I was twelve years old, but yes it does. You get into a zone – I think every artist does – where you have set yourself up about what it is you do then that’s all you’re thinking about. It does happen on a long tour, for instance, but that’s only towards the end of it where you might be thinking about the music. I don’t do much touring these days, so for me, every time I go out it’s a religious experience.

OTM: Is it also a metaphor for the way your life has gone? Anyone watching your film, Everybody Stares, or reading your book can gets a sense that from the moment that motor started, you have just been off to the races ever since.

Pretty much, yes sir I have. A few other things, such as family, rise to prominence in ones life; but yes, that motor is still running and it applies to composition as well as playing, but that’s a different one.

You know, you get up every morning. People wonder about “writer’s block”, which professionals don’t suffer from. You walk in, you fire up your computer and get started. You just do it. Whether or not it’s your best work, you don’t judge, you’re doing work. If needed, you can come back to it later and make it your best work. You have the keys. You turn on the ignition, the engine catches and you’re running.

OTM: You have such an evident joy when you are playing, just a visible enthusiasm.

Well, it is pretty good fun.

OTM: A great example would be in the Better Than Therapy documentary within the “Police Certifiable” DVD set. The band is rehearsing for the reunion tour at Sting’s home studio in Italy and as you launch into “Synchronicity II”, you let out a yell of ‘Whoa!”, as if you’re dropping down the first hill of a roller coaster, almost an exuberant “Here we go!”

Well, what I think that probably is we had actually made it through more than four bars without stopping and discussing it.

OTM: Do you derive the same type of enthusiasm when seeing one of your scores charted out for orchestra, or is it more when you actually hear it performed live?

My greatest excitement is when I hear my computer play it back. This is a personal peccadillo that I would suspect is shared with many composers. The computer has no sensitivity, no humanity, no soul, no emotion and no sympathy! But it plays the fucking notes the way I wrote them. It is absolutely like clockwork. The little intricate interweaving rhythms all just fit perfectly and do their jobs. The different components of the music all interact with each other. You put that on a stand in front of a 90-piece orchestra and it’s in not so sharp a focus, because it has the input of humanity, emotion and everything else.

But that exactitude is never quite the same. So composers may secretly admit that their guilty pleasure is really listening to the computer performances of their work. Now if I’m playing with the orchestra, that’s entirely different. There are two verydifferent characters involved – the drummer dude and the composer dude – and they are almost unrelated and often in conflict.

OTM: Let’s talk about a different ‘composition’ – the work you’ve done with your famous Super 8 camera, with which you documented the rise of The Police. I won’t say fall because The Police never fell. Did you intend for all of that footage to ever become a major production or that it would even be for public consumption?

Oh yeah! When I was shooting it of course! I thought I was Cecil B. Demille. The adventure was so exciting one couldn’t help but get pumped up getting caught up in the circumstance. It’s very easy for you to fall for the notion that one is the living, returning messiah here to bring music upon all the people, and that every utterance, every frame of footage shall become legend. Every band feels that way regardless of whether or not it actually pans out. I’m sure that had any of the other groups around us at that time, had they been shooting film as well, they would have thought the same way too. I got lucky.

OTM: You really sat on the footage for very a long time.

Well, that was due to technology. The Super 8 film has no negative. You only have the master and every time you view the footage running it through a projector, you are scratching it. When you try to edit the film it gets even worse. You lose a frame on each side, you try to tape or glue it together, you gash the film and you can’t change your mind later.

OTM: It took a great deal of patience on your part to wait.

I knew I wanted to make a movie, but I also realized that I would be ruining the footage if I moved forward with the editing. So I just put the project aside while I scratched my head deciding what to do with it. The other thing that happened was, at a certain point, I realized I was shooting it rather than living it, at which point I put down the camera which I bitterly regret. I got us up to the stadiums, but kind of missed the last year. But playing stadiums after awhile is all just more of the same thing. So I put them in a shoebox.

OTM: An actual shoebox?

Yup, my wife wears fancy shoes, which come in fancy boxes and they are actually perfect for storing film. I did try transferring it to video, but it looked like crap on video and then I forgot about them. Then, they invented computers. They invented cheap memory. At that point, Final Cut came along and I have always been an app junkie. I love playing with all of them – PhotoShop, Final Cut Pro, Pro Tools, Digital Performer, After Effects, all these things. I love it.

OTM: So what happened?

I was screwing around with Final Cut and making funny little movies of my kids and such, and for some reason I wondered what it might be like to telecine the footage I had of The Police to digital. It turned out to be kind of reasonable, so I got a couple of reels and then thought, “Shoot, let me do it all!” It was fifty two hours of footage. I ended up doing just a bit of it, cutting a little movie figuring I’m going to show it to Andy (Summers) and so on. It kind of grew and grew to the point when my buddy, Les Claypool, said, “Hey man, you should send it to Sundance!” Well, right there as we were chatting on the phone with our computers open, as folks tend to do, I logged on to the site, paid my fifty bucks, chatted away and forgot about it.

OTM: And then surprise, surprise!

Thanksgiving Eve of that year, I got a call from Sundance telling me they were happy to let me know my film had been accepted into The Sundance Film Festival. I was really excited. When the following Monday came around, that’s when I really got excited! My email was just full of inquiries from Focus Features, Sony Classics, just about every film company and studio, every agent all wanted to see my movie. ICM, William Morris, every publicist was like “I’d like to represent your movie.” It was enormous the response I received and getting on the list for Sundance turned my little movie into and adventure in itself. Even though I shot the footage, I had to go and get permission from everyone in it to use in the documentary. For instance, Andy plays a little song in the dressing room I recorded. Well, that music belongs to Universal. It is an Andy Summers master recording owned by the record company. I had to go and get permission to use it.

OTM: How did that go over?

My first meetings at Universal were of course very polite. We all met in a back room of the Golden Oldies, or maybe they call it the Archives Division, some windowless office in the back. After the Sundance invitation, I go down there and I am in the big boardroom with every vice president of everything at the company with their chests bared and voices raised. “We’re going to do this and we’re going to do that!” It was just an amazing transformation that my little movie had suddenly become “a thing”. The film really didn’t belong to me anymore; it was now this “thing” out there. So I had to finish it, take it to Sundance, and well, the rest is history.

OTM: It is such a great film to watch because you are seeing the band from your personal point of view.

Well thank you!

OTM: Although Rumblefish was your first motion picture score, it wasn’t exactly your first experience with composing music for film. The soundtrack for Brimstone and Treacle in 1982 started it all.

Yes, you are correct. We didn’t really have much contact with the film and didn’t understand what was going on. We just went to the studio. Sting said he needed some music for the film and wanted to see what we’d come up with. The three of us came up with some grooves in the studio. I don’t even think we were looking at footage. There might have been some picture there, but I don’t think so.

OTM: Was your (The Police) involvement with the film only because of Sting’s role in the movie?

Yeah, we just jammed and they took those recordings and cut them into the movie or didn’t. I can’t even remember.

OTM: So those songs were all specific to the film, none of them were laying around waiting to possibly go on the next Police project. Those compositions weren’t being saved for Synchronicity or something?

Not that I was aware of. I’m not sure if Sting had some of those riffs already or if we just came up with them there in the studio.

OTM: The following year, 1983, you receive a phone call from Francis Ford Coppola to score Rumblefish. You have said you really didn’t have any idea what process was involved in composing a score for a major motion picture. That may have actually worked to your advantage. Approximately 30 scores later between film and television, has your process evolved from that first experience or are there some things you still do the same?

Yeah, it has, and technology has made a huge difference. Rumblefish I had to play on my bare hands. There was one computer in the room which was really hifalutin and operated by the guy who invented it. The program calculated BPM (beats per minute) from here to there. The cue starts here and ends there. If you want sixteen bars, it’s this BPM. If you need nineteen bars, it’s that BPM. This computer program was a way of mapping out and giving yourself a click track for the piece of music you would then write. That’s all it did, calculate time and break it down into bars. It was damn clever at the time, cutting edge. Apart from that, I would record everything on two inch analog tape. I had to play every instrument with my bare hands and come up with the shit and record it on the spot.

OTM: The process still must have been quite challenging as opposed to the collaborative process of creating songs for The Police.

It was a very different, less contemplative process. I would have the scene and would have either a guitar or a keyboard and get a rhythm going. I’d continue to look at the scene and build the music, recording it as I was looking at the film scene and kind of doing it that way. When they finally came out with Digital Performer, Fairlight and other composition tools, you were really able to compose music then. Those programs gave the music a little more finesse and allowed you to be a little more specific during the recording process. But for Rumblefish, every overdub was whatever I came up with as I had the particular instrument in my hand.

OTM: Were you composing to the dailies?

No, I was composing to the film itself. Back in the day, they would lock the footage and then everybody in post-production – the sound effects people, the dialogue guy, composer, coloring – those people would get to work. Once a motion picture is locked, it is locked period. If the director changed his mind and wanted to snip a scene, all those departments used to howl. When they invented computers the howling stopped. If a director changes his mind, now they can do it. So in the days of Rumblefish, locked meant locked. These days, the film is just kind of “latched”.

OTM: Hopefully this next subject won’t cause “trouble”, bad pun intended, but the music for the Star Wars Droids cartoon, the theme “Trouble Again”, how did you get that gig?

SC – Oh yes! Droids! Well that was an incoming call from George Lucas this time. It was still in the early days and I didn’t totally understand the process yet. I went to meet with George at his studio. The meeting, however, was not to discuss characters or review scenes of film. On his desk he had rows of toys and that was what the music was for. This is the product, here are the toys. There were two television series. There was Ewoks and there was Droids. Lucas had these two different sets of toys and it was basically “Let’s see what you can come up with.” So I did a bunch of songs – very obscure.

OTM: So with the more recent release of the Star Wars animated series Clone Wars, you didn’t get involved with that?

They didn’t call. I’m really not in that business anymore, though there is a movie coming out for The Equalizer. I wonder if they will use the original theme I scored for the show.

OTM: One would think so if they are going to be true to the premise of the series.

Yeah, I hope so!

OTM: You have touched upon how technology has moved the process of writing for motion pictures rather quickly in terms of writing and scoring scenes. Do you think the proliferation of all these various Internet tools now available to the general public has made the bar for making music too low?

No such thing. There is absolutely no such thing as the threshold being too low. Real music is campfire music – folks, just regular folks sitting around the fire singing together – that’s what music really is. All this other specialization, from which I have been a great beneficiary of course, is kind of departure from the raw essence of what real music is. It’s kind of nice that some guy can go off and play guitar 24-hours a day, get really good at it, then entertain the rest of us with what he spent all day learning how to do. That specialization is not a bad thing, I love it. But real music is just about people making it and sharing it. Basically, ever since primates started banging on a big log in the jungle making the loudest noise – you know the drummer – everything beyond that is an extrapolation. All your guitars, singers, poets and violins, they’re all just extensions of what we (drummers) do. The idea of a separation between the performer and the audience is a later nuance that was introduced.

OTM: That’s a great segue to discuss the videos you post from Sacred Grove!

Oh yeah! That’s kind of primal. You know actually it’s a combination. All the performances you see on there are raw inspiration. There is nothing pre-rehearsed, nothing figured out. People just come up with the shit on the spot. So not only is it live, you’re actually witnessing moments of inspiration. Once I get the jam, then I get out the scissors and Final Cut and massage it and Foley in things you see. If there is some guy blasting on a horn, then I’ll put it in there with some actual music.

OTM: You have had some really heavy hitters come through there to jam with you.

Yeah, word is spreading. I am actually getting incoming calls about it with musicians asking, “Hey, do you have a Sacred Grove Jam coming up any time soon?” I have a bunch of friends that I met on Twitter that are luminary musicians that are dying to come over. It’s kind of been on hiatus because of the Ben-Hur project, but when I get through with all of that, then probably next fall we’ll be getting back into Sacred Grove.

OTM: Now that you have brought it up, let’s get in to your latest project. Why the silent film version of Ben-Hur? What was it about the 1925 film that drew you to it?

Well, that fact was I had already written a shitload of music for a 2009 stage adaptation called Ben-Hur Live was the key. It was this mad German impresario, Franz Abraham, who decided he wanted to put Ben-Hur, the book, on stage and he did it in arenas around Europe. He had a cast of hundreds of underpaid Czechs and Hungarians and they staged the chariot race, the pirate battle, the gladiatorial combat, everything. The whole book was recreated live. Enormous forces were involved. There was a huge light show, the galleys of the ships being dragged around the arena floor. It was a big show, which I believe is still running. In fact, I just got a post card from the producers saying they are headed to Seoul, South Korea.

OTM: That is amazing.

Yeah, but during the process, there was a stock market crash and that German impresario whom everyone thought was mad and is mad, his financial world collapsed. I loved the man, because if it had not been for his crazy vision, none of us would have been there. Turns out he had done a little too much juggling with his money and various things happened to crush him. I actually had to pay the orchestra in Bratislava out of my own back pocket. For various reasons, I ended up owning every inch of the score I had been commissioned to write. The copyright, the master recordings, everything all reverted to me.

OTM: There are all sorts of twists and turns going on here.

After I had acquired the rights to the score, I was thinking I’d like to play concerts with some of this music. I was proud of what I had done. As I was conceiving what kind of show I could put together with Ben-Hur as the backdrop, I received a phone call about scoring the 1925 movie. I watched the silent movie then drank the Kool-Aid. I took the two hour and twenty minute film and cut my music to it whittling everything down to a 90-minute concert. It tells the story of Ben-Hur and of Jesus Christ. Keep in mind the original title of the book was Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. This silent film version has a much stronger religious element to it which is actually pretty powerful. I mean, I’m a Left Coast libertine, but I get it, I get this message. It’s very emotional and very compelling. You still have the horse race, the pirates and everything, but there is a little bit of love and redemption as well.

OTM: When you were preparing your original score for the stage adaptation you were commissioned to write for the arena performances, did you purposely avoid watching the 1950’s version of the Charlton Heston film that Miklos Rozsa had done?

No, it never crossed my mind. I probably haven’t seen that version since the 1950s. I had a different mission. What I had to do was actually perform the script – all the roles, all the narration. Since I didn’t have a movie to work with, I had to create an audio track with a beginning and ending as far as time goes. Only then could I write the music to go with it. The script had suggested timings to work off of. For instance, the Romans charge onto the stage, kick ass, take names and drag off Judah – 20 seconds. I’d read the narration for that scene, acted it out, do a lot of shouting then build an audio scape of what I’d imagine the scene duration to be. Then I’d write the music for that section.

OTM: How did the production translate on stage?

Funny thing happened. By the time they got to the opening night at the O2 Arena in London, they couldn’t get a famous actor to come out to the venue to narrate the show. Sean Connery I guess had declined the role of narrator. In every country the show played in, they would have a narrator come in and translate the scenes in that nation’s language. By this time, the entire cast, the lighting design, the choreographers, everyone basically had been going along with the music during rehearsals. Besides the music, my voice was used to narrate. Everyone had memorized my version of the narration by heart, even the horses. They would hear my voice and know it was time to giddy up!

OTM: This entire production sounds like a mad German really was behind it.

It gets better. Finally one day, the producers look at me and say, “Well, why don’t you do the narration?” And I am going “Moi, are you mad?” Well they were mad and I ended up doing the narration. I rode around the arena on a horse with my voice booming through the speakers, “And so Judah came to Jerusalem!” It was all pretty cool really, with the best part being I had prerecorded it all and mimed the shit! In fact, I would come out and do the introduction, then take Judah’s horse and gallop around the arena. I got a little horse riding in there, looking damn heroic. As far as everyone was concerned, there’s my name on the score with me riding around telling everybody about it. The whole thing looked like it was my production, like it was my show, which it certainly was not. I was just a hired gun composer in those days. But it was a good adventure.

OTM: Despite the unexpected twists and turns, this production sounds like it was a great deal of fun.

It was! It really was! Here was this huge production with enormous forces taking part to create a magnificent spectacle. It was really something.

OTM: Moving toward April 19th in Norfolk, Virginia at the Chrysler Center, what can the audience expect? Obviously you are performing with a full orchestra, the film projecting in real time alongside with you.

Yeah, as I say it’s making its way downstage toward the front. I’m not sure exactly yet where the screens will end up, but the concept of the show is putting more and more emphasis on the movie. I will be there with not one drum set, but two, because that’s how I roll these days. It’s a drum set plus a percussion set.

OTM: So your set-up will be slightly similar to what you used on The Police reunion tour?

Yes! It’s very, very similar – not exactly the same deal, but that’s the idea. But wait, I want to tell you a fun story about curating the film.

OTM: Go right ahead.

It took two years to work through the labyrinth of Warner Brothers, who own this property. When we finally got the permission, we dug out the old print and it’s an 80-year old print. It took two weeks to defrost and then digitize. The film had not been seen since the ‘60s when they burned it to video. This venerable ancient can is coming out of deep freeze and when I got the actual footage, I’m looking at not just the frame, but the sprockets on the sides, the whole thing.

OTM: You went above and beyond the call of duty to score this project.

I had to curate the film, address the faded black and white sections of the footage as well as the tints from the ‘20s that they had applied at the time by dipping it in an amber wash or magenta wash. I had to reproduce all of those. Now there’s another huge process of curating the film – framing it. I had to get the contrast right, reproduce those colors as well as editing it down and trying to tell the story in just 90 minutes. That was quite an adventure, all done off the original celluloid. This is very different than what you would see on the DVD. It’s a much more beautiful image.

OTM: Do you see any filming, or recording and publishing of this venture?

Well, it may be considered to be crossing a line. I’m sure if I chewed on it for some time I could figure out a logic way to do it. But for the moment, it’s a concert. So I don’t feel too bad about taking Fred Niblo’s masterpiece and cutting it and carving it because it’s a concert. It would be a strange animal (a DVD release) too. What would be on the screen, the orchestra with a little sidebar of a movie?

OTM: Are you considering this a one off show or will you take it elsewhere?

Oh no! The Chicago Symphony is on board and will take it on in October. With Chicago on board, I’m sure several other orchestras will shake loose. We’ll see where it goes!